| Home |

Le Général |

It wasn't that long ago I had the great privilege of interviewing a real hero, Gad Beck, who as a young gay man during the Second World War became the leader of Chug Chaluzi - the Pioneer Group - which helped feed, shelter and transport over 100 Jews as part of the Europe-wide resistance movement Hechaluz, the Pioneers.

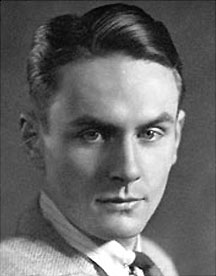

But I have learnt that for many, life in the German trenches was just as horrifying, especially if you were gay. Which is why I wanted to interview Montreal artist Peter Flinsch, who was born in Leipzig, Germany, in 1920 and was conscripted into the German anti-aircraft artillery of the Luftwaffe in 1938.

"I wanted to become an architect but you were obliged to do two years of military service," Flinsch tells me in the art- and plant-filled downtown Montreal apartment where he has lived the last 32 years. "But as you know, the war started in 1939 and I was only released in 1945."

Flinsch, meanwhile, realized he was gay when he turned 18, during school before he was conscripted. But, like Gad Beck, he had to be extremely discreet because Paragraph 175 of the archaic German penal code empowered the Gestapo to round up all suspected faggots and imprison them in concentration camps. (It wasn't until 1998 that Germany pardoned those rounded up under Paragraph 175.)

"All these concepts today about gay identity did not exist back then," Flinsch explains. "The term homosexual was known, but when I myself approach my past, I have to try to forget the things we know now because it was different back then in Germany. You could not talk about [gay life] as we do today. We just did not talk about it."

That didn't save Flinsch, who was arrested after he was spotted embracing another man. "I was supposed to become an officer on January 1, 1943, and I was stationed in Berlin. The air raids were starting to get more heavy but Berlin was not destroyed yet. After a Christmas party, Christmas 1942, my friend and I embraced and kissed and we were seen by somebody from my unit. I was arrested, I was 22 years old and they told me the old trick, 'Admit your guilt and we'll be lenient.' So I fell for it and I was court-martialled."

Flinsch was sentenced to serve in a disciplinary unit made up of 'criminals' whose job was to clear mines on the front lines. "It was a death command," he says softly. "I was not sent to the concentration camps. Only civilians were sent to the concentration camps. I was treated badly and broke down and was hospitalized. But my family stood behind me. Without my family I would not have survived."

As for Berlin, the city he left almost 60 years ago, Flinsch returned for a month. He returned home to Montreal just last week. "It was wonderful going to gay bars in Montreal [after the war] after what I'd been through in Germany," Flinsch winds down. "There was no gay life in Berlin back then, but there is now. But it's not as concentrated as Montreal. I must say, Montreal tops them all - it's concentrated, like headquarters.

"But you know, if you had told me when I was in prison that I would be sitting here talking to you about gay life 60 or 70 years later, I would not have believed it."